As these new crisis bailouts for fossil fuels show, it’s those who are least deserving who get the most government protection

Those of us who predicted, during the first years of this century, an imminent peak in global oil supplies could not have been more wrong. People like the energy consultant Daniel Yergin, with whom I disputed the topic, appear to have been right: growth, he said, would continue for many years, unless governments intervened.

Oil appeared to peak in the United States in 1970, after which production fell for 40 years. That, we assumed, was the end of the story. But through fracking and horizontal drilling, production last year returned to the level it reached in 1969. Twelve years ago, the Texas oil tycoon T Boone Pickens announced that “never again will we pump more than 82 million barrels”. By the end of 2015, daily world production reached 97m .

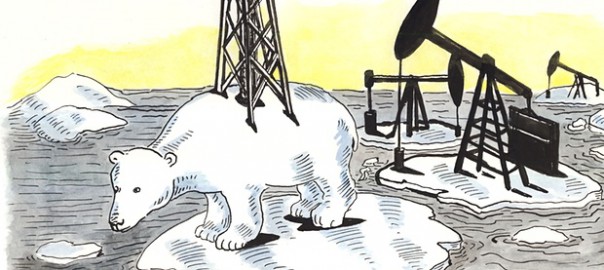

Instead of a collapse in the supply of oil, we confront the opposite crisis: we’re drowning in the stuff. The reasons for the price crash – an astonishing slide from $115 a barrel to less than $30 over the past 20 months – are complex: among them are weaker demand in China and a strong dollar. But an analysis by the World Bank finds that changes in supply have been a much greater factor than changes in demand. Oil production has almost doubled in Iraq, as well as in the US. Saudi Arabia has opened its taps, to try to destroy the competition and sustain its market share – a strategy that some peak oil advocates once argued was impossible.

The outcomes are mixed. Cheaper oil means that more will be burned, accelerating climate breakdown. But it also means less investment in future production. Already, $380 billion that was to have been ploughed into oil and gas fields has been delayed. The first places to be spared are those in which extraction is most difficult or hazardous. Fragile ecosystems in the Arctic, in rainforests, in remote and stormy seas, have been granted a stay of execution.

Read more: The Guardian