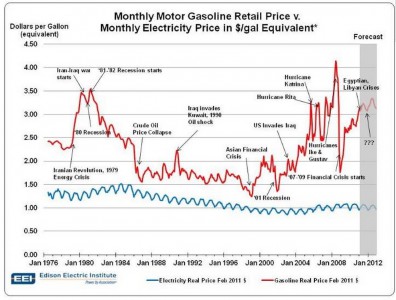

From 2010 to 2014, U.S. electric car sales surged from almost nothing to about 120,000 per year. But the haters and doubters persist. Analysts and investing forums are buzzing about a coming stagnation. After all, in the past seven months the price of oil has collapsed from $115 a barrel to below $50. Gasoline prices have plummeted, too, fast approaching $2 per gallon nationally, and commuters are rejoicing. That means a key selling point for electric vehicles — low fuel costs — is gone. The electric car appears to be in trouble.

Surprisingly, it is not. This past week, the floor of the North American International Auto Show in Detroit was stacked with glitzy new electric cars, from the BMW i3 to the Chevrolet Bolt to SUVs and micro-cars. That’s because today’s electric car boom isn’t really about oil prices at all; it’s about clean air. Under the leadership of California, a group of environmentally progressive states (Oregon, New York, Maryland, Massachusetts, Vermont, Rhode Island and Connecticut) has created market-based mandates that set a floor under the electric-vehicle market. In other words, they’re forcing automakers to sell electric cars. The goal is to have 3.3 million of them on their roads by 2025. Thanks to clever policy design, the survival of electric cars doesn’t depend on the vagaries of the global oil market.

For more than a century, electric cars have repeatedly lost out to oil. As early as the 1890s, electric taxi fleets were stealing market share from horse-and-buggy drivers in New York, Philadelphia and Atlantic City. Even Thomas Edison was in on the game, spending more than a decade — and $1 million of his own fortune — developing a battery technology aimed at electric cars.

Electric cars, however, couldn’t keep pace with the fast-improving internal combustion engine. Its range, power and portability were all superior, thanks to oil. By 1910, Henry Ford (a former Edison Illuminating Company employee) had effectively crushed the early electric car. By 1927, half of all American families owned an oil-fueled car. Electric cars were no longer serious contenders.

But between 1969 and 1979, oil prices spiked, reviving interest in electric cars. In 1975, Congress took up a bill called the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Research, Development, and Demonstration Act, which included $30 million for studies and deployment. A year later, Congress overrode a presidential veto to authorize $160 million for electric-vehicle research and testing over a five-year period. But when oil prices plummeted in the 1980s, policymakers retreated, halting funding for research.

Today, pessimists see a depressingly familiar pattern: Energy prices spike; huge sums of capital flow from the government and the private sector into oil alternatives; energy markets crash; those funds vanish and industries wither. And, of course, the electric car dies.

What makes California different is that its electric-car program isn’t tied to oil prices — because the project predates the oil shocks by more than two decades. After World War II, a mysterious pall of smog strangled Los Angeles. California’s response was to build a potent architecture for researching and regulating air pollution. This eventually became the California Air Resources Board (CARB), a body that rapidly outpaced the federal government in the science and policy of pollution control.

By 1970, California’s regulatory infrastructure was so developed that the national Clean Air Act allowed the state to set its own standards for emissions — and gave other states the option to follow its strict guidelines in lieu of those set by the federal government. If automakers wanted to sell cars in California — or in other states with similar regulations — their vehicles had to adhere to California’s emissions standards. These efforts accelerated in 1975 when Gov. Jerry Brown installed a new, aggressive chairman, Tom Quinn, at the state Air Resources Board. For a decade, CARB focused on cleaning up the exhaust from combustion engines. In 1990, with oil prices around $20 a barrel, CARB went even further, setting its sights on a car that didn’t pollute at all: a zero-emissions vehicle, an electric car.

California mandated that a certain percentage of cars sold in the state had to be electric — initially 2 percent by 1998 and escalating to 10 percent by 2003 — and then set about building a long-range strategic plan to help automakers fulfill the mandate. One key element was creating a market for car companies to buy and sell zero-emissions vehicle (ZEV) credits issued by the state for electric vehicle sales. If one automaker failed to sell electric cars, it could buy credits from a competitor who had succeeded. While building electric cars was expensive, so was buying credits; it also took a toll on a company’s reputation and deprived manufacturers of the technological insights they would gain by developing the cars. The incentives for automakers to push forward were in place.

Implementing the mandate was a long, iterative process, and the regulators’ initial goals proved to be overly ambitious. Over the decades CARB muddled through lawsuits and high-stakes policy brawls with automakers and the George W. Bush administration. Carmakers grumbled that California could not simply mandate innovation. “I wish that, instead of zero-pollution vehicles, CARB had mandated a cure for cancer,” Automotive News sneered. Then, for years, the Bush administration refused to grant California regulators a federal waiver for emission standards that until then had been practically pro forma.

But California kept going. Because the state was America’s largest auto market, it was too big for carmakers to abandon.

In 2010, automakers began selling a new generation of truly mass-produced electric vehicles, starting with the Nissan Leaf. California’s market for credits rewarded companies such as Tesla and Nissan that got out in front. These companies have reaped hundreds of millions of dollars from selling credits to laggards that did not fulfill their quotas. In the third quarter of 2014, Tesla Motors earned $76 million on ZEV credits alone.

California has also rewarded buyers of electric cars. It granted cash incentives to early adopters and gave them access to high-occupancy vehicle lanes so they could bypass the daily crush of rush hour. And California helped other states design their own incentive programs, which include perks such as rebates, free city parking and in some places free charging. The benefits make electric cars more attractive financially, particularly since the upfront costs of purchasing one might not be offset by fuel savings for years.

Today America is the world’s largest market for electric cars, and about 90 percent of them are sold in states following California’s program. The project took time to develop, but it finally broke the link between innovation policies and the capricious commodity cycle. The electric-car effort is just the kind of strategic planning that will be needed to transition away from fossil fuels, avoid the next oil shock and drive America toward a clean-energy economy.

Electric-vehicle sales may sag for a month or a quarter, but will cheap oil kill the electric revolution? Don’t bet on it. Electric cars are here to stay.

Source: Washington Post