The business world is finally waking up

If you hear a lot of noise about climate policies and climate action over the next few months in the lead up to the Paris climate conference, it is because there is a lot at stake. According to Citigroup analysts: $US100 trillion of potential stranded assets in the fossil fuel industry.

A new Citigroup report values the fossil fuel reserves that need to be left in the ground if the world is to meet its targets of trying to limit global warming to 2°C – a target that, according to a new Climate Council report, is actually a lot less “safe” for humankind than the science thought it was just 10 years ago.

Nevertheless, that is the stated target of all governments – including Australia’s – and Paris will endeavour to put in place a mechanism that will allow the world to meet that goal.

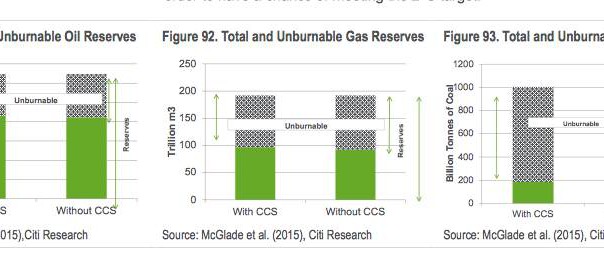

But if the world is serious about meeting this target, it needs to respect its “carbon budget” – and that calls for one-third of global oil reserves, one half of global gas reserves, and 80 per cent of global coal reserves to remain in the ground.

This graph sums up the findings of a new analysis published this year in Nature by McGlade and Ekins. The green represents the percentage of the various fossil fuel types that could be extracted under a 2C scenario.

Translating that into dollar terms, and using metrics of $US70 per barrel of oil, $US6.50/MMBTU of gas (an average weighted price of US, European and Asian prices) and $US70 per tonne of coal, that amounts to a lot of money.

“We estimate that the total value of stranded assets could be over $US100 trillion based on current market prices,” Citigroup notes in the report. And coal bears the brunt, accounting for more than half the value of stranded assets, even in the unlikely event that carbon capture and storage becomes a viable technology.

Read more: Renew Economy