Many reasons have been provided for the dramatic plunge in the price of oil to about $60 per barrel (nearly half of what it was a year ago): slowing demand due to global economic stagnation; overproduction at shale fields in the United States; the decision of the Saudis and other Middle Eastern OPEC producers to maintain output at current levels (presumably to punish higher-cost producers in the U.S. and elsewhere); and the increased value of the dollar relative to other currencies. There is, however, one reason that’s not being discussed, and yet it could be the most important of all: the complete collapse of Big Oil’s production-maximizing business model.

Until last fall, when the price decline gathered momentum, the oil giants were operating at full throttle, pumping out more petroleum every day. They did so, of course, in part to profit from the high prices. For most of the previous six years, Brent crude, the international benchmark for crude oil, had been selling at $100 or higher. But Big Oil was also operating according to a business model that assumed an ever-increasing demand for its products, however costly they might be to produce and refine. This meant that no fossil fuel reserves, no potential source of supply — no matter how remote or hard to reach, how far offshore or deeply buried, how encased in rock — was deemed untouchable in the mad scramble to increase output and profits.

In recent years, this output-maximizing strategy had, in turn, generated historic wealth for the giant oil companies. Exxon, the largest U.S.-based oil firm, earned an eye-popping $32.6 billion in 2013 alone, more than any other American company except for Apple. Chevron, the second biggest oil firm, posted earnings of $21.4 billion that same year. State-owned companies like Saudi Aramco and Russia’s Rosneft also reaped mammoth profits.

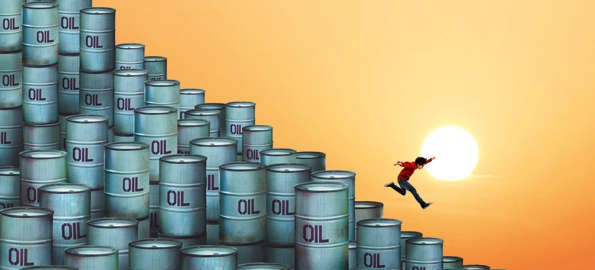

How things have changed in a matter of mere months. With demand stagnant and excess production the story of the moment, the very strategy that had generated record-breaking profits has suddenly become hopelessly dysfunctional.

To fully appreciate the nature of the energy industry’s predicament, it’s necessary to go back a decade, to 2005, when the production-maximizing strategy was first adopted. At that time, Big Oil faced a critical juncture. On the one hand, many existing oil fields were being depleted at a torrid pace, leading experts to predict an imminent “peak” in global oil production, followed by an irreversible decline. On the other, rapid economic growth in China, India, and other developing nations was pushing demand for fossil fuels into the stratosphere. In those same years, concern over climate change was also beginning to gather momentum, threatening the future of Big Oil and generating pressures to invest in alternative forms of energy.

A “Brave New World” of tough oil

No one better captured that moment than David O’Reilly, the chair and CEO of Chevron. “Our industry is at a strategic inflection point, a unique place in our history,” he told a gathering of oil executives that February. “The most visible element of this new equation,” he explained in what some observers dubbed his “Brave New World” address, “is that relative to demand, oil is no longer in plentiful supply.” Even though China was sucking up oil, coal, and natural gas supplies at a staggering rate, he had a message for that country and the world: “The era of easy access to energy is over.”

To prosper in such an environment, O’Reilly explained, the oil industry would have to adopt a new strategy. It would have to look beyond the easy-to-reach sources that had powered it in the past and make massive investments in the extraction of what the industry calls “unconventional oil” and what I labeled at the time “tough oil”: resources located far offshore, in the threatening environments of the far north, in politically dangerous places like Iraq, or in unyielding rock formations like shale. “Increasingly,” O’Reilly insisted, “future supplies will have to be found in ultradeep water and other remote areas, development projects that will ultimately require new technology and trillions of dollars of investment in new infrastructure.”

For top industry officials like O’Reilly, it seemed evident that Big Oil had no choice in the matter. It would have to invest those needed trillions in tough-oil projects or lose ground to other sources of energy, drying up its stream of profits. True, the cost of extracting unconventional oil would be much greater than from easier-to-reach conventional reserves (not to mention more environmentally hazardous), but that would be the world’s problem, not theirs. “Collectively, we are stepping up to this challenge,” O’Reilly declared. “The industry is making significant investments to build additional capacity for future production.”

On this basis, Chevron, Exxon, Royal Dutch Shell, and other major firms indeed invested enormous amounts of money and resources in a growing unconventional oil and gas race, an extraordinary saga I described in my book The Race for What’s Left. Some, including Chevron and Shell, started drilling in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico; others, including Exxon, commenced operations in the Arctic and eastern Siberia. Virtually every one of them began exploiting U.S. shale reserves via hydro-fracking.

Only one top executive questioned this drill-baby-drill approach: John Browne, then the chief executive of BP. Claiming that the science of climate change had become too convincing to deny, Browne argued that Big Energy would have to look “beyond petroleum” and put major resources into alternative sources of supply. “Climate change is an issue which raises fundamental questions about the relationship between companies and society as a whole, and between one generation and the next,” he had declared as early as 2002. For BP, he indicated, that meant developing wind power, solar power, and biofuels.

Browne, however, was eased out of BP in 2007 just as Big Oil’s output-maximizing business model was taking off, and his successor, Tony Hayward, quickly abandoned the “beyond petroleum” approach. “Some may question whether so much of the [world’s energy] growth needs to come from fossil fuels,” he said in 2009. “But here it is vital that we face up to the harsh reality [of energy availability].” Despite the growing emphasis on renewables, “we still foresee 80 percent of energy coming from fossil fuels in 2030.”

Under Hayward’s leadership, BP largely discontinued its research into alternative forms of energy and reaffirmed its commitment to the production of oil and gas, the tougher the better. Following in the footsteps of other giant firms, BP hustled into the Arctic, the deep water of the Gulf of Mexico, and Canadian tar sands, a particularly carbon-dirty and messy-to-produce form of energy. In its drive to become the leading producer in the Gulf, BP rushed the exploration of a deep offshore field it called Macondo, triggering the Deepwater Horizon blow-out of April 2010 and the devastating oil spill of monumental proportions that followed.

Over the cliff

By the end of the first decade of this century, Big Oil was united in its embrace of its new production-maximizing, drill-baby-drill approach. It made the necessary investments, perfected new technology for extracting tough oil, and did indeed triumph over the decline of existing, “easy oil” deposits. In those years, it managed to ramp up production in remarkable ways, bringing ever more hard-to-reach oil reservoirs online.

According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA) of the U.S. Department of Energy, world oil production rose from 85.1 million barrels per day in 2005 to 92.9 million in 2014, despite the continuing decline of many legacy fields in North America and the Middle East. Claiming that industry investments in new drilling technologies had vanquished the specter of oil scarcity, BP’s latest CEO, Bob Dudley, assured the world only a year ago that Big Oil was going places and the only thing that had “peaked” was “the theory of peak oil.”

That, of course, was just before oil prices took their leap off the cliff, bringing instantly into question the wisdom of continuing to pump out record levels of petroleum. The production-maximizing strategy crafted by O’Reilly and his fellow CEOs rested on three fundamental assumptions that, year after year, demand would keep climbing; that such rising demand would ensure prices high enough to justify costly investments in unconventional oil; and that concern over climate change would in no significant way alter the equation. Today, none of these assumptions holds true.

Demand will continue to rise — that’s undeniable, given expected growth in world income and population — but not at the pace to which Big Oil has become accustomed. Consider this: In 2005, when many of the major investments in unconventional oil were getting under way, the EIA projected that global oil demand would reach 103.2 million barrels per day in 2015; now, it’s lowered that figure for this year to only 93.1 million barrels. Those 10 million “lost” barrels per day in expected consumption may not seem like a lot, given the total figure, but keep in mind that Big Oil’s multibillion-dollar investments in tough energy were predicated on all that added demand materializing, thereby generating the kind of high prices needed to offset the increasing costs of extraction. With so much anticipated demand vanishing, however, prices were bound to collapse.

Current indications suggest that consumption will continue to fall short of expectations in the years to come. In an assessment of future trends released last month, the EIA reported that, thanks to deteriorating global economic conditions, many countries will experience either a slower rate of growth or an actual reduction in consumption. While still inching up, Chinese consumption, for instance, is expected to grow by only 0.3 million barrels per day this year and next — a far cry from the 0.5 million barrel increase it posted in 2011 and 2012 and its 1 million barrel increase in 2010. In Europe and Japan, meanwhile, consumption is actually expected to fall over the next two years.

And this slowdown in demand is likely to persist well beyond 2016, suggests the International Energy Agency (IEA), an arm of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (the club of rich industrialized nations). While lower gasoline prices may spur increased consumption in the United States and a few other nations, it predicted, most countries will experience no such lift and so “the recent price decline is expected to have only a marginal impact on global demand growth for the remainder of the decade.”

This being the case, the IEA believes that oil prices will only average about $55 per barrel in 2015 and not reach $73 again until 2020. Such figures fall far below what would be needed to justify continued investment in and exploitation of tough-oil options like Canadian tar sands, Arctic oil, and many shale projects. Indeed, the financial press is now full of reports on stalled or cancelled mega-energy projects. Shell, for example, announced in January that it had abandoned plans for a $6.5 billion petrochemical plant in Qatar, citing “the current economic climate prevailing in the energy industry.” At the same time, Chevron shelved its plan to drill in the Arctic waters of the Beaufort Sea, while Norway’s Statoil turned its back on drilling in Greenland.

There is, as well, another factor that threatens the well-being of Big Oil: Climate change can no longer be discounted in any future energy business model. The pressures to deal with a phenomenon that could quite literally destroy human civilization are growing. Although Big Oil has spent massive amounts of money over the years in a campaign to raise doubts about the science of climate change, more and more people globally are starting to worry about its effects — extreme weather patterns, extreme storms, extreme drought, rising sea levels, and the like — and demanding that governments take action to reduce the magnitude of the threat.

Europe has already adopted plans to lower carbon emissions by 20 percent from 1990 levels by 2020 and to achieve even greater reductions in the following decades. China, while still increasing its reliance on fossil fuels, has at least finally pledged to cap the growth of its carbon emissions by 2030 and to increase renewable energy sources to 20 percent of total energy use by then. In the United States, increasingly stringent automobile fuel-efficiency standards will require that cars sold in 2025 achieve an average of 54.5 miles per gallon, reducing U.S. oil demand by 2.2 million barrels per day. (Of course, the Republican-controlled Congress — heavily subsidized by Big Oil — will do everything it can to eradicate curbs on fossil fuel consumption.)

Still, however inadequate the response to the dangers of climate change thus far, the issue is on the energy map and its influence on policy globally can only increase. Whether Big Oil is ready to admit it or not, alternative energy is now on the planetary agenda and there’s no turning back from that. “It is a different world than it was the last time we saw an oil-price plunge,” said IEA Executive Director Maria van der Hoeven in February, referring to the 2008 economic meltdown. “Emerging economies, notably China, have entered less oil-intensive stages of development … On top of this, concerns about climate change are influencing energy policies [and so] renewables are increasingly pervasive.”

The oil industry is, of course, hoping that the current price plunge will soon reverse itself and that its now-crumbling maximizing-output model will make a comeback along with $100-per-barrel price levels. But these hopes for the return of “normality” are likely energy pipe dreams. As van der Hoeven suggests, the world has changed in significant ways, in the process obliterating the very foundations on which Big Oil’s production-maximizing strategy rested. The oil giants will either have to adapt to new circumstances, while scaling back their operations, or face takeover challenges from more nimble and aggressive firms.

Source: Tom’s Dispatch via Grist